EXHIBITIONS

Mark Divo

Mark DivoBanned in Facebook

Paintings and Installations

01 November - 30 December 2019

Mark Divo’s singular creative vision has been demonstrated in the exemplary exhibitions that have been shown at underground art spaces and hippie festivals over the past few years.

This exhibition aims to deftly unearth the depths of his work by presenting two new paintings and a kinetic installation which are formally distant from each other but quite closely related through his explorations of abstraction. The Installation 'The enigma of compassion' follows in this vein exploring lesser-known terrain of the artist's practice in kinetic art. The kinetic installation 'the enigma of compassion' consists of a series of electronically animated sculptures that mimic human organs.

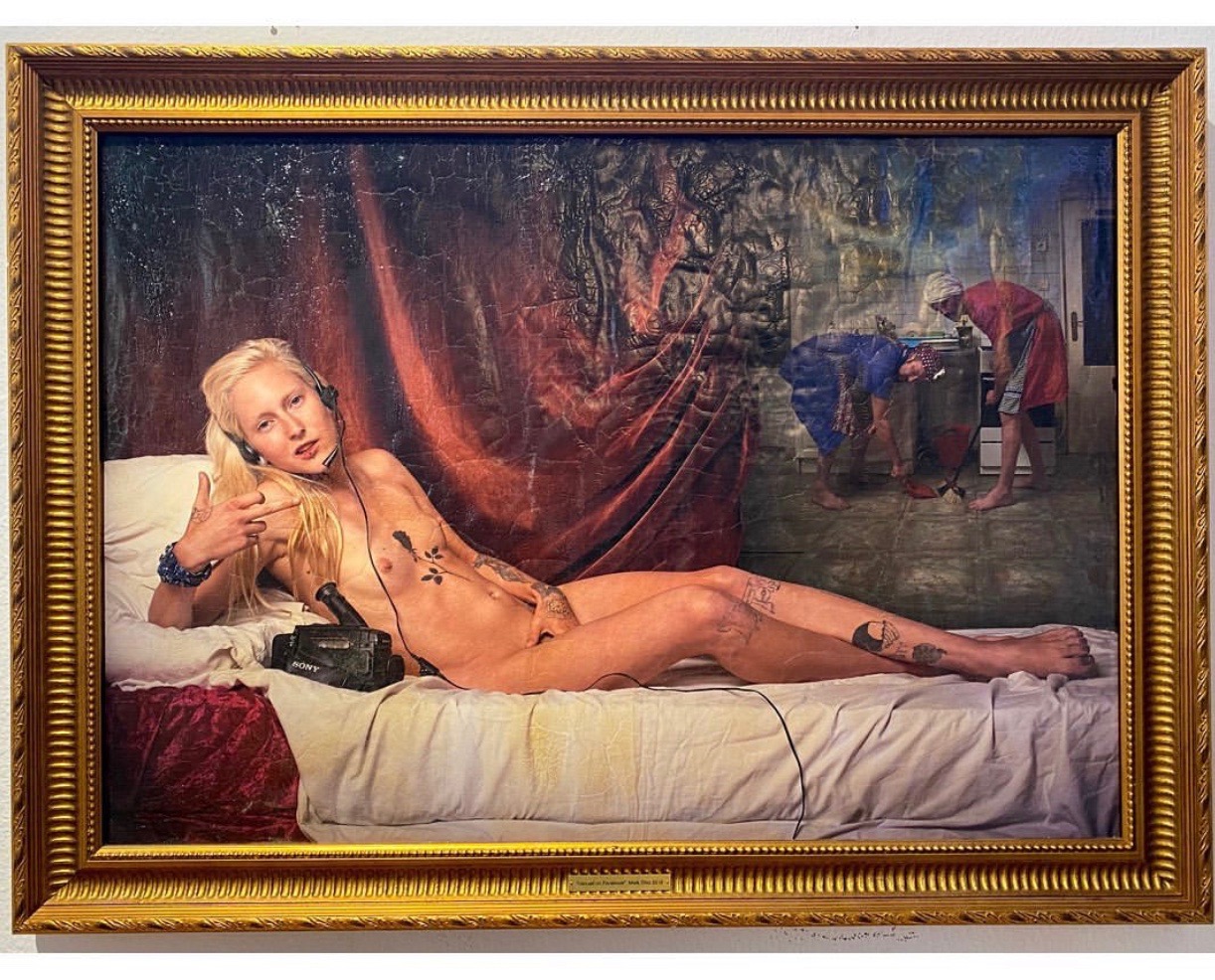

The picture 'Banned on Facebook' completed in 2019 is very interesting for its many hidden meanings.

The painting represents the allegory of hypocrisy in social media. The evident eroticism of the painting, in fact, reminds of the obligations women are thought to have to fulfil in an oversaturated late capitalist society. The erotic allegory is evident in the representation of the internet prostitute, the victim of consumerism, as a sensual and delectable woman staring at the viewer who could not ignore her beauty. The light and warm colour of her body are in contrast to the gesture of her hand sticking up the finger, bringing out her eroticism.

The headset and the video camera at the hand of the woman are the symbols of commercial exploitation while, in the background, two crossdressed housemaids are sweeping the kitchen floor-this symbolises the hypocrisy of an oversexed but at the same time prudent society. The strong sensuality of this painting is therefore consistent with its political meaning as an attack on conventional norms.

The set up of the picture is a tribute to Titian, who in 1538 had painted a very similar subject, the Venus of Urbino. Thanks to the wise use of colour and its contrasts, as well as the subtle meanings and allusions. Divo achieves the goal of representing the perfect late-capitalist women who, unlike Venus, becomes the symbol of exploitation, pornography and prostitution.

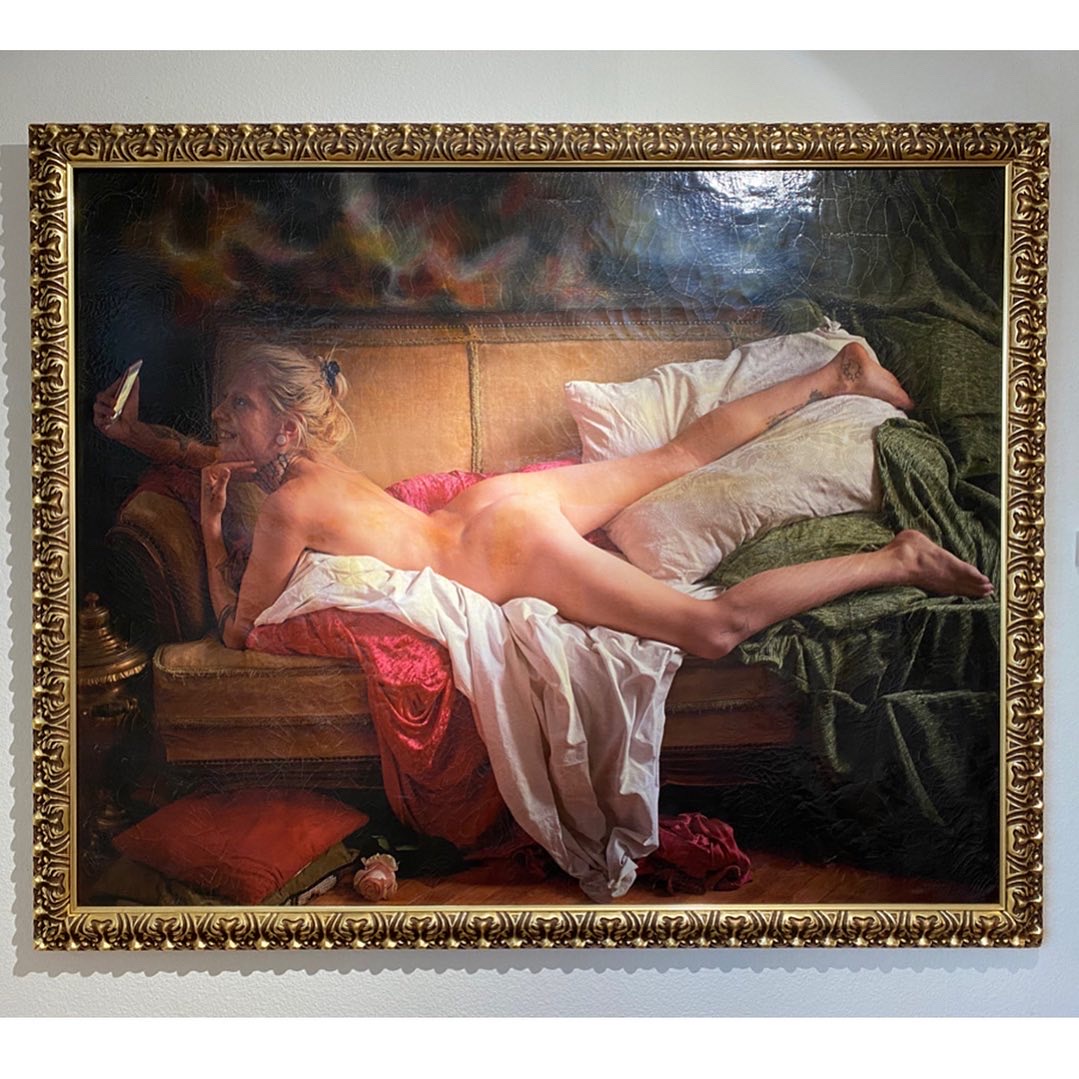

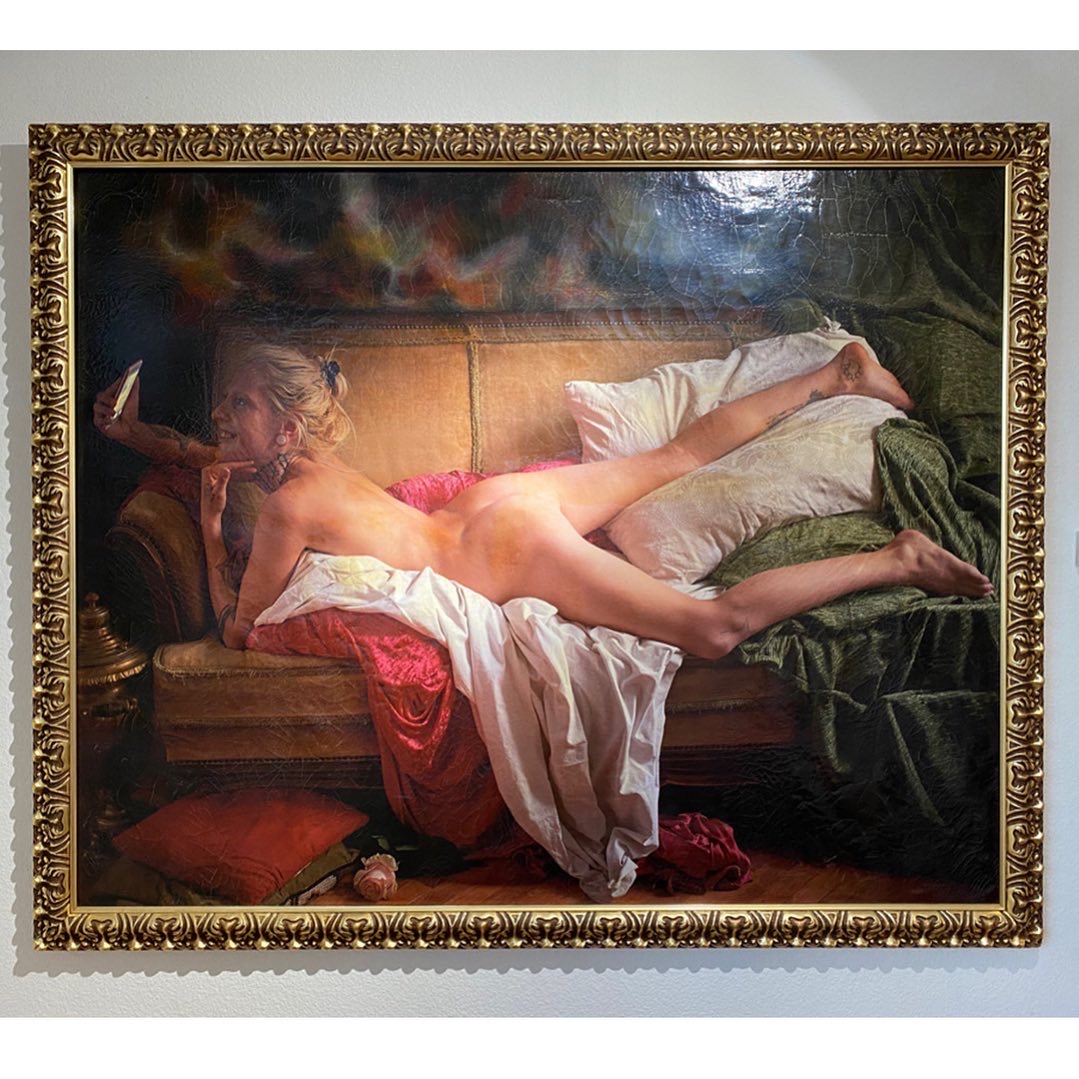

The second painting has the title 'Selfish' and is one of the more sexually provocative pictures in the canon. Its subject is lying naked and splayed on a daybed taking a selfie of herself. The focus of the picture "Selfish" is on the buttocks. But that's not precisely where the provocation lies. This picture also offers buttocks with wide-open legs – a direct invitation to penetrate. But they're also where the painting gets most interesting. If you look at the contours of the two buttocks, the two legs and the pillow, you find an interplay of curves and tucks and creases and outlines and overlaps.

All that formal activity is designed to keep your eye on this spot. But it's also a kind of distraction. You now see the body in terms of the shapes it's making. You lose touch with its anatomy. At the sexual centre of the painting, pictorial interest and sexual interest are in conflict.

Divo’s priorities are divided. The contemporary artist in him may want to make a statement that's political. But the social commentator can't help being excited by its potential as a composition involving a cellphone. Each way the model is "objectified" – but in two different and diverging ways and when it comes to "objectifying", painting is always an unstable medium. It tends to blur the distinction between the animate and the inanimate. It treats living creatures like objects – and invests objects with life.

Look at the girl's left hand. holding the cellphone, but then, look at the tumultuous bedding and the cascading curtain, which writhe and strain and press as if possessed by a muscular, anatomical life. The pillow pushes up between the girl's legs. There's an echo of mythological scenes where the god Jupiter impregnates a nymph in the form of a cloud or a shower of gold.

The art of painting, in other words, has its own compulsions. It's not very good at making proper moral distinctions between persons and things. The whole physical world tends to get mixed up, with life circulating through it promiscuously. But painting isn't very good at doing pure sociology either. Its political meaning is always getting distracted by naked bottoms.

WORKS

If you cannot find here the work you have seen at the exhibition, please contact info@mondejargallery.com or call/text +41 76 577 0854. Thank you.

Selfish, 2019, 160 x 130 cm Oil on canvas

Banned on Facebook, 2019, 84 x 114 cm Mixed Media/Oil on Canvas